Some people we’ve told about our current donor egg IVF attempt automatically assume that this cycle will work — that we will walk away with a baby. While we are certainly way more optimistic about this cycle than our previous three (non-donor-egg) cycles, unfortunately, the odds are still not 100%…not even close. So in the interest of managing everyone’s expectations, what are the odds of this donor egg IVF cycle working?

I won’t leave you in suspense: the answer is 25%.

Yep. 25%. Depressing, right?

Of course, the exact value will depend on the quality and quantity of eggs they get from our egg donor, Marie. But given her age and the number of eggs they aim for, we are going through all of this effort — multiple international flights, daily injections, disrupting four peoples’ work schedules, and spending thousands of euros — for a one-in-four shot. In other words, don’t get out your baby booty knitting pattern just yet.

So how is this value calculated? As I said above, the two main factors are egg quality and egg quantity. Egg quality decreases with age, where the AMH level can give a rough indication. Marie has a fairly normal AMH level for her age (even a bit above average), but she is still 36. So as high-quality as her eggs may be, we can’t expect them to compare with those of an 18-year-old.

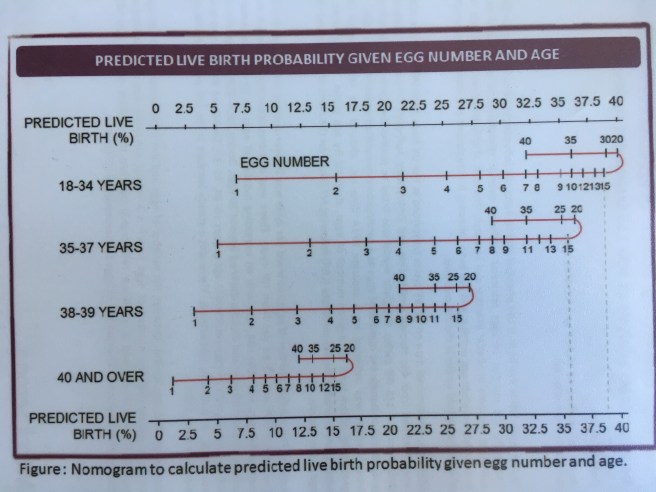

By egg quantity, I mean the number of eggs that Marie grows during the stimulation cycle. I had previously read that they aimed for 10-12 eggs in an IVF cycle. However, apparently 15 eggs is already getting into the territory of ovarian hyper-stimulation syndrome (OHSS), which can cause complications for the donor (in addition to decreasing the quality of the resulting eggs). In order to steer clear of those complications (and since it’s not a very exact science), our clinic will aim for 6 eggs in this cycle. Combining this number of eggs with Marie’s age, we arrive at a 25% chance of it working.

All of this is nicely summarized by this chart from my doctor, which I snapped a (poor-quality) picture of at our last appointment. It shows the predicted live birth rate as a function of age and egg number. The important thing to notice is how the live birth rate starts decreasing again above 15 eggs. Even with a younger donor, this would limit our success rate to 30% (for 6 eggs) or 40% in the very best case of exactly 15 eggs.

In summary, not only are the odds not 100%, but it’s actually likely that this cycle won’t result in a baby. We will continue to be cautiously optimistic, but don’t expect me to be googling gender-reveal cake recipes quite yet.